In the Tate series, Movements in Modern Art – Conceptual Art, author Paul Wood writes, “One of the features of successful Conceptual art is how a major shift is made with the apparent minimum of means, as if doing almost nothing can, if the circumstances are right, turn the world on its axis.”

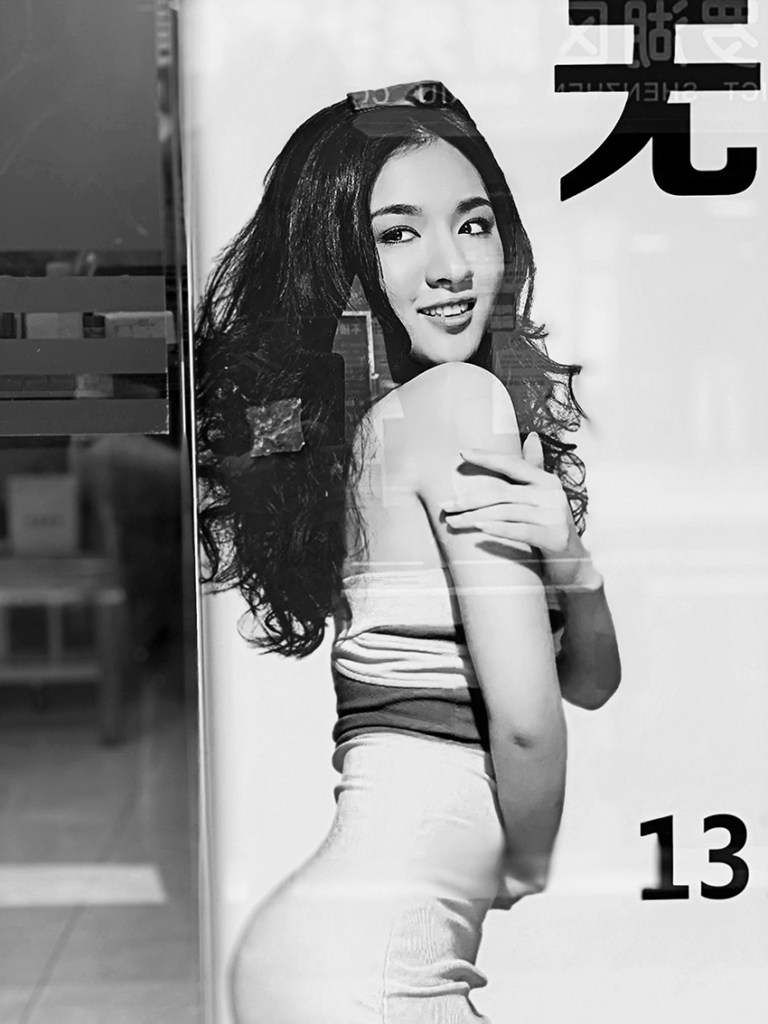

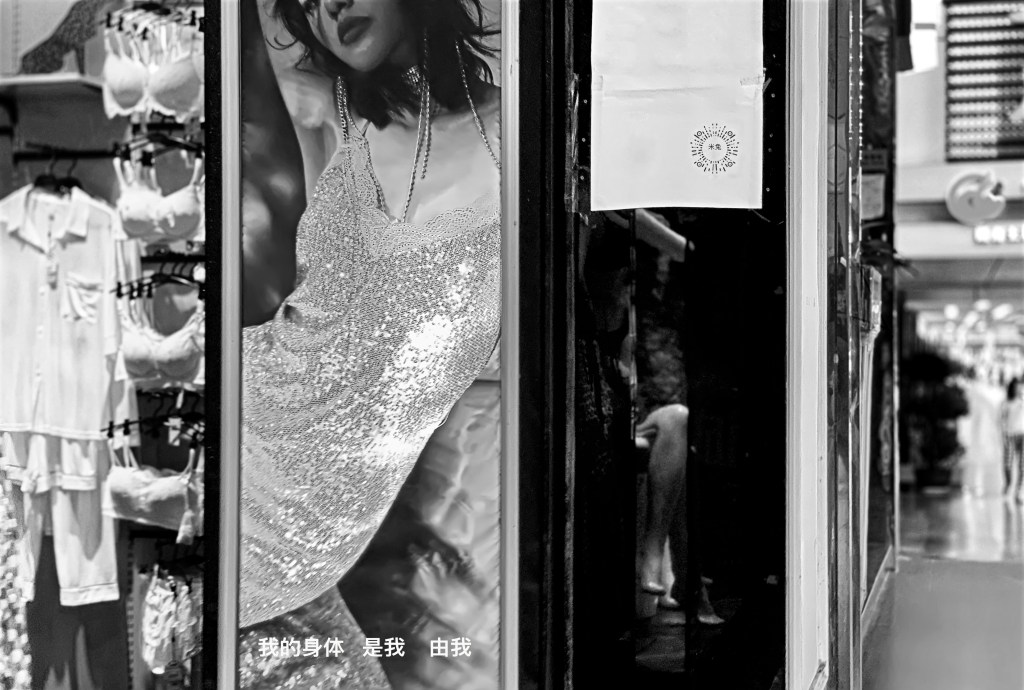

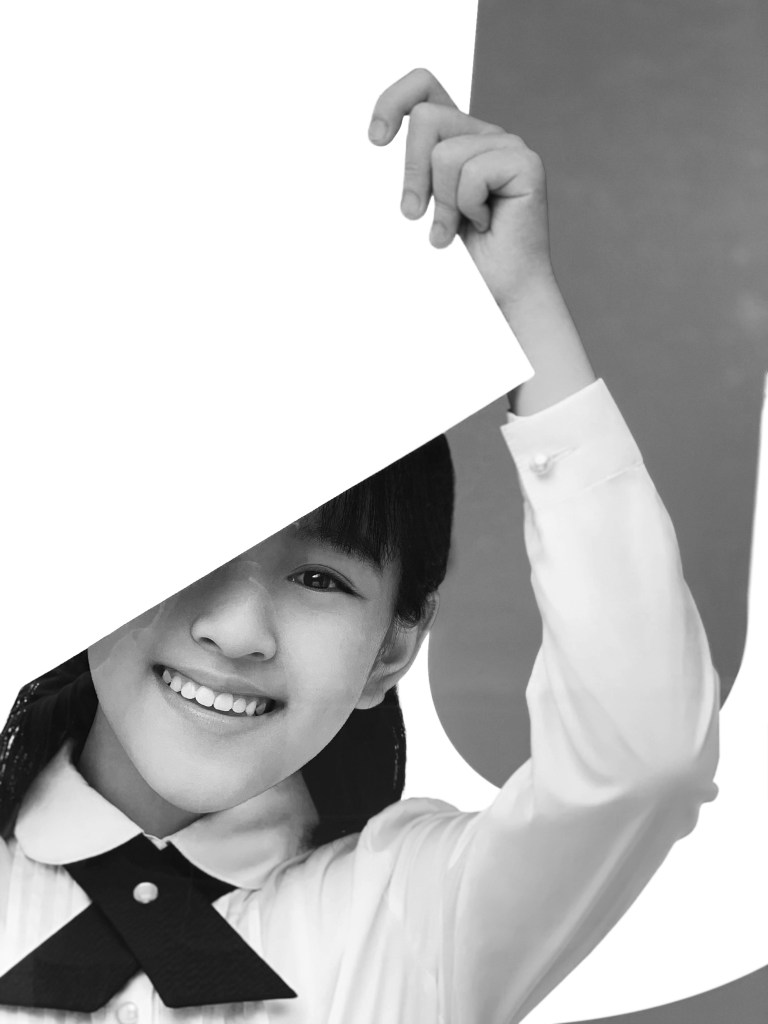

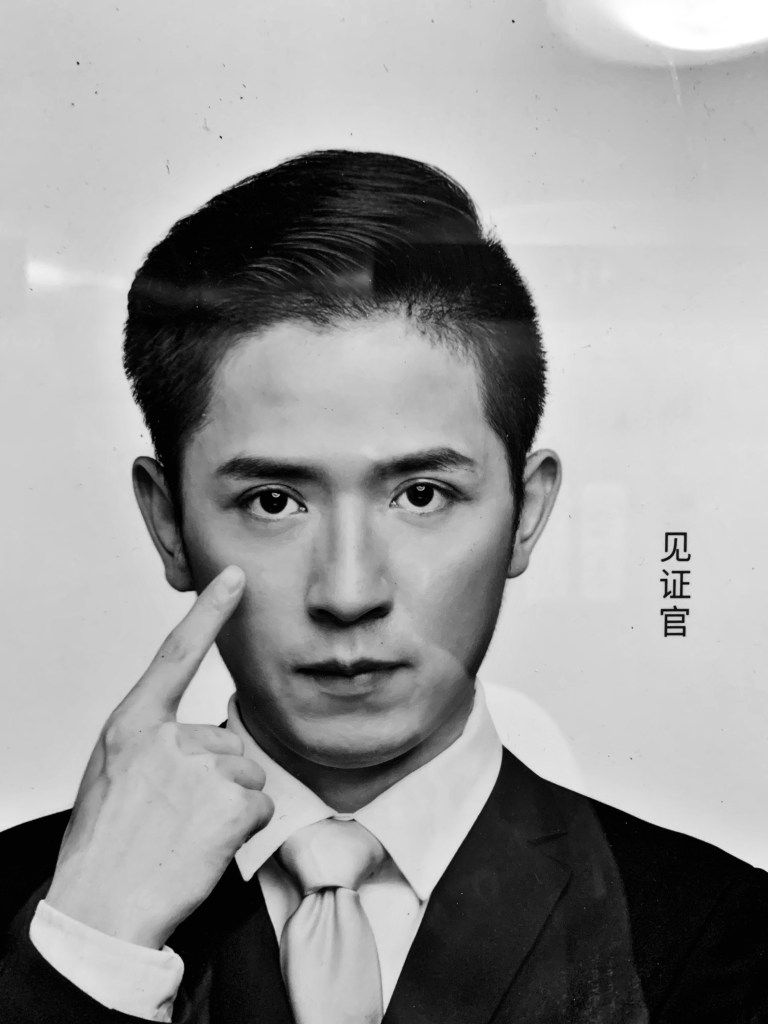

With this image, as with the others in this series of appropriated images, it is the idea that matters most. These photographs are conceptually driven, but the craft and aesthetics of each image, from the moment of shooting through post processing, is carefully considered.

Like the photographs of Walker Evans, they are shot in a documentary style; they use the vernacular of the photographic document to examine culture through a critical lens. They have the form and look of information, but are intended more as visual poetry than prose.

These are appropriated lens-based images, but contextual variables at time of shooting and post-processing decisions alter them from the original.

Like Moriyama, I do not recognize a border between ‘lived reality’ and the ‘reality of the image.’ The latter is a part of the former.